Are the Poor Left Behind Or Are the Rich Simply Pulling Ahead?

Education prepares a child for a productive participation in society. In fact, education among some individuals, including myself, has served as a vehicle out of poverty. In fact, without the solid basic education I have received from Centro Escolar University, Quiapo Parochial School, and the Manila Science High School, I would not be where I am. This may sound similar to President Obama's story, but my mother likewise used to wake me up early in the morning to study. I was indeed fortunate to have parents who truly valued education. While I was growing up, studying was actually a good excuse to get out of household chores. The combination of good elementary teachers and parents who valued education truly provided me with an excellent head start. With education having a significant impact on the future of a child, equity in education is clearly an issue that needs to be addressed.

I now live in the United States and my wife and I are raising two children, one is six years old, currently in first grade, and another, who is three years old and is attending preschool. I can look back at myself when I was the same age as my son. I also entered first grade when I was six years old. My son and I could both read and do simple math at this age. My son is doing as well as his classmates. In fact, everyone in my son's class seems to be on a trajectory to master all the standards set for first grade. I, on the other hand, was one of the stars in the class. I stood out. Surprisingly, my son actually knows more and performs better on various tasks compared to myself when I was at his age. My comparisons do not stop here. Final exams are around the corner. I look back at my first year at the Ateneo and compare myself with my current students. My students certainly have covered more topics than I did when I was a freshman. Of course, these are anecdotal, but research actually agrees with these observations. Sean F. Reardon, a professor of education and sociology at Stanford University, recently wrote an opinion article, "No Rich Child Left Behind", where he mentioned:

"The average 9-year-old today has math skills equal to those their parents had at age 11, a two-year improvement in a single generation."I am not going to disagree. And Reardon's conclusion above is based on average test scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, not on anecdotes. Reardon's article on the New York Times is a synopsis of the research that he has done on this topic over the past years. For example, some of Reardon's work is presented in a 2011 book entitled "Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances". The title of Seardon's chapter is "The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations". The following is its abstract:

Abstract

In this chapter I examine whether and how the relationship between family socioeconomic characteristics and academic achievement has changed during the last fifty years. In particular, I investigate the extent to which the rising income inequality of the last four decades has been paralleled by a similar increase in the income achievement gradient. As the income gap between high- and low-income families has widened, has the achievement gap between children in high- and low-income families also widened?

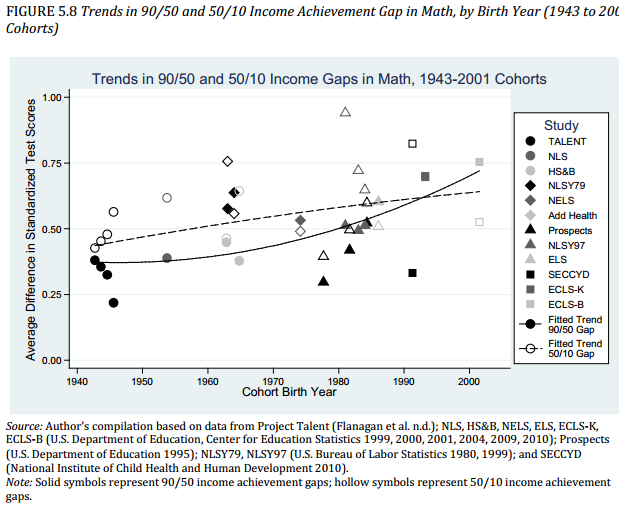

The answer, in brief, is yes. The achievement gap between children from high- and low income families is roughly 30 to 40 percent larger among children born in 2001 than among those born twenty-five years earlier. In fact, it appears that the income achievement gap has been growing for at least fifty years, though the data are less certain for cohorts of children born before 1970. In this chapter, I describe and discuss these trends in some detail. In addition to the key finding that the income achievement gap appears to have widened substantially, there are a number of other important findings.

First, the income achievement gap (defined here as the income difference between a child from a family at the 90th percentile of the family income distribution and a child from a family at the 10th percentile) is now nearly twice as large as the black-white achievement gap. Fifty years ago, in contrast, the black-white gap was one and a half to two times as large as the income gap.The following figures from this paper tell a very interesting story:

Second, as Greg Duncan and Katherine Magnuson note in chapter 3 of this volume, the income achievement gap is large when children enter kindergarten and does not appear to grow (or narrow) appreciably as children progress through school. Third, although rising income inequality may play a role in the growing income achievement gap, it does not appear to be the dominant factor. The gap appears to have grown at least partly because of an increase in the association between family income and children’s academic achievement for families above the median income level: a given difference in family incomes now corresponds to a 30 to 60 percent larger difference in achievement than it did for children born in the 1970s. Moreover, evidence from other studies suggests that this may be in part a result of increasing parental investment in children’s cognitive development. Finally, the growing income achievement gap does not appear to be a result of a growing achievement gap between children with highly and less-educated parents. Indeed, the relationship between parental education and children’s achievement has remained relatively stable during the last fifty years, whereas the relationship between income and achievement has grown sharply. Family income is now nearly as strong as parental education in predicting children’s achievement.

The academic gap is widening because rich students are increasingly entering kindergarten much better prepared to succeed in school than middle-class students. This difference in preparation persists through elementary and high school.Parents who can afford to provide cognitive enriching activities to young children are doing so. This is the head start right before formal schooling. The poor are not being left behind, the rich are simply a leg ahead. Reardon thus concludes with the following:

So how can we move toward a society in which educational success is not so strongly linked to family background? Maybe we should take a lesson from the rich and invest much more heavily as a society in our children’s educational opportunities from the day they are born. Investments in early-childhood education pay very high societal dividends. That means investing in developing high-quality child care and preschool that is available to poor and middle-class children. It also means recruiting and training a cadre of skilled preschool teachers and child care providers. These are not new ideas, but we have to stop talking about how expensive and difficult they are to implement and just get on with it.

But we need to do much more than expand and improve preschool and child care. There is a lot of discussion these days about investing in teachers and “improving teacher quality,” but improving the quality of our parenting and of our children’s earliest environments may be even more important. Let’s invest in parents so they can better invest in their children.The data presented by Reardon are actually promising in the sense that these provide proof that helping children prepare for school is possible. The wealthy is able to do it.

Applying a similar treatment to study the current situation in the Philippines will probably yield similar results. In spite of isolated academic achievements of some poor children, poor children in the Philippines are probably doing worse than children from rich families. Seardon did find that schools in the United States seem to have a very small effect on the achievement gap. In the Philippines, this may not be true. With kindergarten in public schools provided by volunteers, with basic education grossly underfunded especially in poor communities, it is likely that schools in the Philippines may in fact be contributing significantly in the academic achievement gap between rich and poor. I would not be surprised to see that in the Philippines, not only are the rich pulling ahead, but the poor are left behind.

Well, truly said, education not only improves the skill of a person but, it also helps the person to develop his hidden skills and develop confidence in oneself.

ReplyDelete--Francois Sainfort