NCLB: No Country Left Behind

"Critical Thinking" is not necessarily criticizing the person behind the lectern. We all have a tendency to begin with our own ideas which are shaped by our own interests, experiences and understanding. It is this tendency that makes it quite difficult for us not to be selective in the arguments we choose. We only see what we would like to see. Critical thinking, unfortunately, is not equivalent to rejecting claims when these do not agree with whatever we want to see. Critical thinking begins with neither a rejection nor a blind acceptance of a claim. Critical thinking must always starts with recognizing the credibility of the source and apparent validity of the claim.

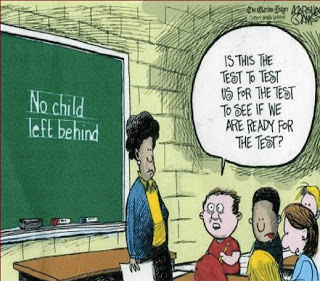

Last Spring semester I had the opportunity to teach a class whose students are among the first generation that has completely gone through the "No Child Left Behind" era in the United States.

|

| Above cartoon copied from American Society Today |

Though the impact has been strongest on American k-12 schools (No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top), the impact is felt in colleges and universities, too. “Learning outcomes” are one of the results, attempts to quantify just about everything and to justify specific learning activities rather than seeing a student as a whole being and an education as something that prepares students for their own explorations, for development of their own ‘learning outcomes.’ This is the factory model of education and, frankly, it has no place in a democracy, where education is supposed to produce participants in the public square who can examine evidence and make decisions on their own. That this ability also makes for better workers is critical to the success of both education and the United States, but the primary focus is on creating good citizens.

We college professors, with problems enough of our own–with changes in governance heading toward a corporate model of top-down decision making, with academic freedom becoming a narrower and narrower aspect of our lives, with more and more of us living and working as contingent and part-time hires, keeping us barely on the fringes of the middle class (if there at all)–haven’t been paying enough attention, as a group, to what has been happening to the schools that feed students to us. Yes, many of us have noticed that our students (especially at non-elite public institutions) are coming to us less and less prepared for college work each ensuing year, but we haven’t put in the time to really explore why. It is hard enough trying to make up for the lacks our students are coming in with. How, furthermore, can we have the time to advocate for changes in k-12 curricula when our own are under fire?

Good question.

I can’t answer it, other than to say that we need to make that time, one way or another.

Things are starting to change, in the k-12 debate, but the “reformers” who want to remake our schools into factories still dominate the discussion. Things they put forward, the the Common Core Curriculum, are accepted as “good” on their faces, without real national discussion and without even testing through pilot programs. Concepts they advocate, like merit pay, vouchers, and even charter schools, have never been shown to improve education–neither has their new idea of rating both schools and teachers, closing and firing those who don’t measure up.What to do with education is definitely an arena where critical thinking must be applied. Yet, the lack of evidence based research backing reforms in education is so widespread. Education reforms have been reduced to attractive slogans such as "No Child Left Behind". Often, reforms have been guided by metrics that have nothing to do with the quality of education. These are numbers that seem to support arguments we like and we simply embrace them. And there are numbers we also see but choose to ignore because these simply do not support what we have selected to be correct. This is not "critical thinking".

We, the professors who see first the results of all of the “reforms” to public education, need to start speaking up.

We also need to learn a little more about what is going on....

The year 2015 is fast approaching. It is the year that the countries belonging to the Association of SouthEast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will see free movement of goods, services, investment, labor, and capitals within the region. Christina Yan Zhang of QSIntelligence Unit writes in "The Rise of Glocal Education: ASEAN Countries":

Student mobility, credit transfers, quality assurance and research clusters were identified as the four main priorities to harmonize the ASEAN higher education system, encompassing 6,500 higher education institutions and 12 million students in 10 nations. The ultimate goal of the scheme is to set up a Common Space of Higher Education in Southeast Asia.With these priorities, the thinking that instinctively follows is "No Country Left Behind". In fact, the ASEAN integration is one of the arguments used to support adding two years to Philippine basic education. Like the NCLB version in the US, this thinking likewise misses what is critical. Former member of the Philippine Congress, Raymond V. Palatino, nicely sums up what seems to be oblivious to so many in his article, "Rethinking ASEAN Integration":

ASEAN unity will remain an impossible vision as long as its members continue to demand it for the wrong reasons. In truth, each member nation views its association with ASEAN as a means to pursue its national interests. Sacrificing the national agenda to realize the regional good is largely an alien concept to ASEAN members. Member nations are in favor of unity as long as it doesn’t conflict with their respective national objectives.ASEAN integration is so much more than just student mobility, credit transfers, quality assurance, and research clusters. "No Country Left Behind" should not be the guiding policy since it reduces the issue into metrics that are in fact irrelevant. By itself, the Philippines is already as diverse as the nations in southeast Asia. The Philippines, an archipelago of more than 7000 islands, is also a country with hundreds of languages. It is supposed to be one nation, yet it remains so bitterly divided in so many ways.

During my college years, I listened to my instructors carefully. I trusted my professors. I even followed one advice given by a chemistry professor, "If you do not understand, memorize. It will help you later." My professors in chemistry really had only one intention - to teach chemistry. They are credible. On education reforms as well as integration of cultures and countries, I must, however, pause. I am no longer inside a classroom with a credible authority behind the lectern. Here, we must strictly adhere to "critical thinking".

Comments

Post a Comment