Copying What Works

There is nothing inherently wrong in copying what other countries do to address challenges in basic education. Even Pasi Sahlberg of Finland acknowledges this in an article published in the Washington Post. The following innovations from the United States are mentioned for their effectiveness in other countries: 1) more observation and description in secondary school science lessons;

2) more individualized reading instruction in primary school classrooms;

3) more use of answer explanation in primary mathematics;

4) more relating of primary school lessons to everyday life; and

5) more text interpretation in primary lessons. Ironically, the United States has not gained so much from these innovations because of its current obsession on accountability and standardized testing.

There are practices that work and there are those that do not. What is obviously important is that one copies only the proven ones. And as important, from the lessons learned in the United States, focusing on those that work is key. A wrong emphasis or preoccupation can thwart even the best innovation. Practices that work often target specific problems. Thus, copying what works can be facilitated by looking at those which address similar challenges.

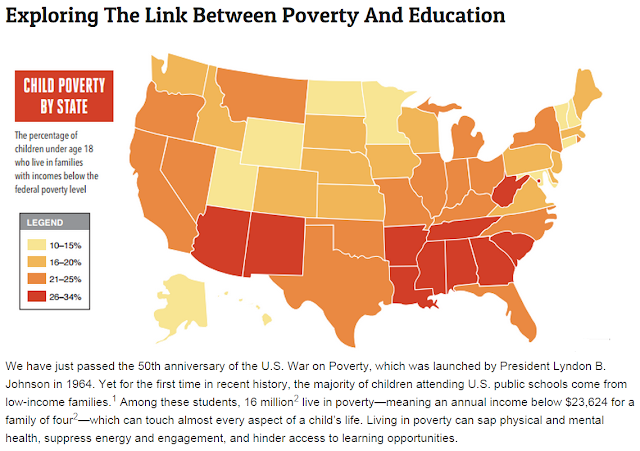

It is now clearer than ever that poverty is a huge challenge to education. The Philippines with its very high poverty incidence cannot deny this very important challenge in its public school system. It is therefore heartbreaking that instead of looking for practices abroad that specifically address poverty, the country has chosen to adopt spiral progression, learning styles, discovery-based instruction, and other questionable innovations. The government in the Philippines has embraced global competitiveness while ignoring the huge inequity in its society. While aspiring for excellence, the country has failed in providing quality education for all. Poverty is not something that can be addressed by simply adding years to basic education or tinkering with the curriculum.

There is poverty in the United States. It is therefore not surprising to see schools in the United States that serve mostly poor children. Learning outcomes in these schools are often below average, but among these poor schools, there are a few high-performing ones. Thus, it is helpful to look at these high-poverty and yet high-performing schools to get a glance at what works in addressing poverty in basic education. An article recently posted on the ASCD blog nicely summarizes what practices have been proven to be effective in these good schools.

The proven practices are as follows (listed with the challenges addressed):

There are practices that work and there are those that do not. What is obviously important is that one copies only the proven ones. And as important, from the lessons learned in the United States, focusing on those that work is key. A wrong emphasis or preoccupation can thwart even the best innovation. Practices that work often target specific problems. Thus, copying what works can be facilitated by looking at those which address similar challenges.

It is now clearer than ever that poverty is a huge challenge to education. The Philippines with its very high poverty incidence cannot deny this very important challenge in its public school system. It is therefore heartbreaking that instead of looking for practices abroad that specifically address poverty, the country has chosen to adopt spiral progression, learning styles, discovery-based instruction, and other questionable innovations. The government in the Philippines has embraced global competitiveness while ignoring the huge inequity in its society. While aspiring for excellence, the country has failed in providing quality education for all. Poverty is not something that can be addressed by simply adding years to basic education or tinkering with the curriculum.

There is poverty in the United States. It is therefore not surprising to see schools in the United States that serve mostly poor children. Learning outcomes in these schools are often below average, but among these poor schools, there are a few high-performing ones. Thus, it is helpful to look at these high-poverty and yet high-performing schools to get a glance at what works in addressing poverty in basic education. An article recently posted on the ASCD blog nicely summarizes what practices have been proven to be effective in these good schools.

The proven practices are as follows (listed with the challenges addressed):

- providing students while they are in school access to a dentist, physician, optometrist, and counselors (physical and mental health)

- addressing and improving the school climate (absenteeism, truancy, bullying)

- use of advisory periods, small learning environments, and culturally-relevant curricula (lack of engagement)

- mentorship programs (lack of support outside school)

- challenging coursework with support (lack of access to quality education)

Of course, one must keep in mind that these are schools in the United States, which are quite different from those in the Philippines. What one can easily copy from the above is the perspective that effective solutions really come from those that address specific problems. The above challenges are not exclusive to the United States. These challenges exist inside Philippine schools. DepEd's K to 12, with its spiral progression, learning styles, discovery-based instruction, and other questionable innovations, does not really address these challenges. Poverty is a huge factor in Philippine basic education. We can learn from other countries. But this will only happen, if we acknowledge what our real problems are.

Thank you for this post man. its very informative.

ReplyDeleteFreeCouponDeals