The Problem With Reading

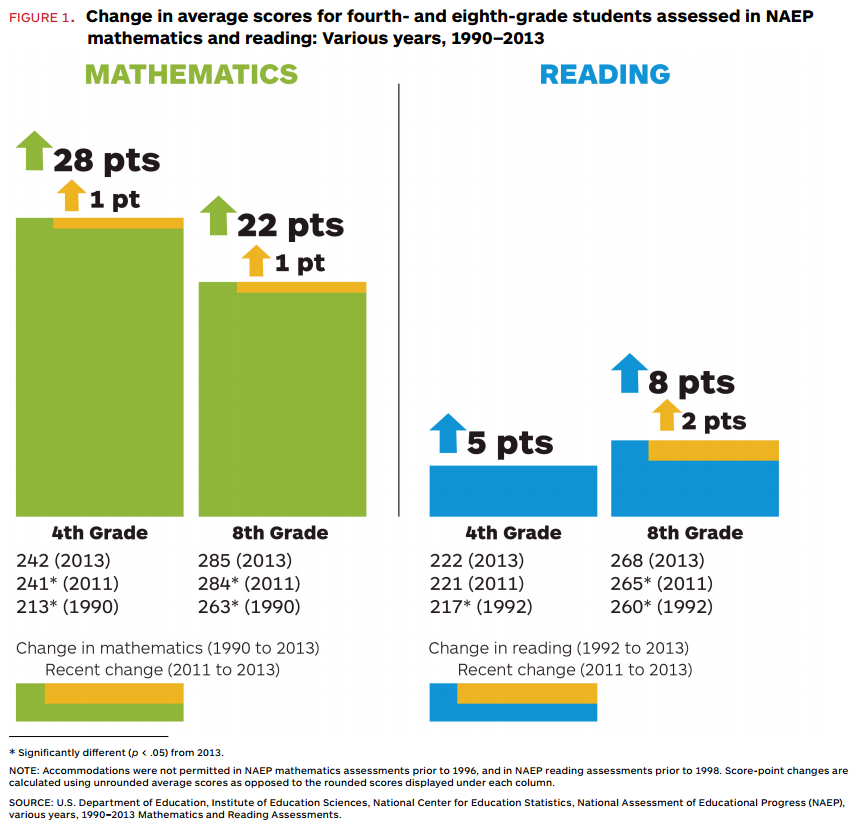

Like mathematics, learning to read is an essential part of basic education. Reading, after all, is an important gateway to the other disciplines. Unfortunately, compared to mathematics, students in the United States have not improved as much in reading comprehension. Based on the results of National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exams, progress in reading comprehension is lagging behind the improvement in mathematics over the past two decades.

The uninspiring growth in reading scores becomes even more evident when one looks beyond the mean scores and examines how scores are distributed throughout the past years.

The bars for math in the figure above when combined start to look like a parallelogram while the bars for reading look very much like a rectangle. Over the past twenty years, the percent of students reaching basic level in math has grown from 48 to 82 percent. In reading, the growth is much less spectacular, from 60 to 67 percent. In 1990, only 12 percent of students have reached proficiency in math. In 2013, 42 percent are now proficient. On the other hand, in reading, over twenty years, the percentage of students reaching proficiency grew from 27 to only 34 percent. Looking at these numbers, one may reasonably infer that we may be doing something right in teaching math. Conversely, we may not be doing something right in reading.

Since reading, like math, is one of the subjects in high-stakes standardized tests, there is no doubt that schools are paying close attention and extra effort on teaching students how to read. There are several "reading comprehension strategies" that should now be quite familiar especially to those who have children enrolled in elementary schools. The following graphic from TeachThought shows some of the popular ones:

These strategies are not new. An article published in 1991 in the journal Review of Educational Research mentions several of these strategies. The article, "Moving from the Old to the New: Research on Reading Comprehension Instruction", lists the following strategies:

The uninspiring growth in reading scores becomes even more evident when one looks beyond the mean scores and examines how scores are distributed throughout the past years.

The bars for math in the figure above when combined start to look like a parallelogram while the bars for reading look very much like a rectangle. Over the past twenty years, the percent of students reaching basic level in math has grown from 48 to 82 percent. In reading, the growth is much less spectacular, from 60 to 67 percent. In 1990, only 12 percent of students have reached proficiency in math. In 2013, 42 percent are now proficient. On the other hand, in reading, over twenty years, the percentage of students reaching proficiency grew from 27 to only 34 percent. Looking at these numbers, one may reasonably infer that we may be doing something right in teaching math. Conversely, we may not be doing something right in reading.

Since reading, like math, is one of the subjects in high-stakes standardized tests, there is no doubt that schools are paying close attention and extra effort on teaching students how to read. There are several "reading comprehension strategies" that should now be quite familiar especially to those who have children enrolled in elementary schools. The following graphic from TeachThought shows some of the popular ones:

These strategies are not new. An article published in 1991 in the journal Review of Educational Research mentions several of these strategies. The article, "Moving from the Old to the New: Research on Reading Comprehension Instruction", lists the following strategies:

- Determining Importance. This is no different from separating the important from the unimportant. This could be achieved by (as suggested in the graphic above) locating key words, activating prior knowledge, and using context clues.

- Summarizing Information. This one is actually in the graphic above.

- Drawing Inferences. This likewise is in the above poster.

- Generating Questions.

- Monitoring Comprehension. This is basically equivalent to evaluating understanding.

These strategies are "somehow" supported by research. The following excerpt from the review's conclusions provides a general overview of research in reading comprehension strategies in the 90's:

We have learned much about the reading comprehension process and about comprehension instruction in recent years, but even more awaits our study. For example, regarding the issue of what to teach, which of the strategies we have identified are necessary and sufficient for the improvement of comprehension abilities? What has been left out? How do strategies develop over time? Even though strategies look similar at different levels of sophistication, should they be introduced differently? Most strategy training work has been completed in the middle and secondary schools. Should strategies be emphasized at the very beginning reading stages, and, if so, which ones can young children be expected to understand and make use of? We also do not know how much of the comprehension curriculum should be spent on the teaching of reading strategies versus other types of activities. How, for example, should strategy instruction time be balanced against such things as decoding skills, free reading, authentic reading and writing activities, and teacher-led discussions of stories?

Fast forward to the current year, the NAEP scores in reading answers most of the questions posed above.

Part of the difficulty is that the strategies have been drawn by assuming that we actually know what good readers do and that reading comprehension can be dissected into various parts, each one necessitating a particular strategy. Reading comprehension is really complex. Kendeou and coworkers have pointed out in "A Cognitive View of Reading Comprehension: Implications for Reading Difficulties", that with children in the early elementary grades, there is a need to take into account developmental differences in children in the following areas:

- Inference making

- Executive functions

- Attention allocations

These areas clearly overlap with most of the strategies commonly suggested to teach reading comprehension. This is a very important point since it illustrates that the strategies a teacher is using to help reading comprehension are actually traits that already require a set of skills. These strategies need to be taught and should not be expected from a child. With this realization, Kendeou and coworkers have suggested that instructional materials, the text a child reads, must be chosen judiciously. Appropriate reading materials must be picked to help children acquire skills in these areas. During the early years, one must not mixed text intended for reading instruction and text intended for gaining knowledge. Secondly, these skills are not limited to reading text. Children must be given the opportunity to exercise these skills while listening or even watching a show or movie. Third, reading is a process, therefore it is important that instruction goes along with the reading, not just before or after, but more importantly, during reading. Lastly, background information is often influential in reading comprehension that an instructor must always take this into account.

Lastly, in the journal The Reading Teacher, Shanahan reminds us of much older techniques that may help students develop reading comprehension. The article, "Let's Get Higher Scores on These New Assessments", enumerate the following:

- Interpretation of vocabulary in context

- Making sense of sentences

- Sustained silent reading

Shanahan concludes:

"The idea of having students practice answering test questions is ubiquitous and ineffective in raising test scores. Consider focusing instruction on those things that actually make a difference in test performance. Teach kids how to figure out the meanings of words on the basis of morphology and context. Teach them to figure out the meanings of complex sentences by breaking those sentences into parts. Teach them to sustain their concentration during the silent reading of challenging and extensive texts. Teach those things well, and you will see improved test performance; the side benefit to be derived from this kind of test prep would be that your students would become better readers to boot."

If a child does not have a strategy we expect, reading becomes only frustrating, hurting the child's love for reading. We must develop and not expect these strategies from children. Focusing on strategies that we think good readers should have may not be an effective way of teaching. It is like teaching arithmetic while expecting that a child already knows numbers and how to add and subtract.

Comments

Post a Comment