Teamwork Versus Excellence: Is This Another False Dichotomy?

On one hand, we read that working together leads to better results. Take for example, a post from the blog of the United States Department of Education where a quote from a public school teacher in Springdale, Arkansas is highlighted: "I used to think about just my classroom. Now, I care about the collective whole of fourth grade." Teamwork, according to the principal in this school, has led to substantial gains in student learning simply by having teachers work as a team and believing that each student can succeed at very high levels.

Watching the video above leaves me with the following phrases:

"We have teachers that believe in each and every student and their potential."

"We make all decisions at our school based on what the data tell us."

"We are able to separate our students into who is doing really well, who is at grade level, and who is not, but not what it means by the child, but what it means by our teaching."

"There is no shame in reaching out for help."

"We really focus on growth."

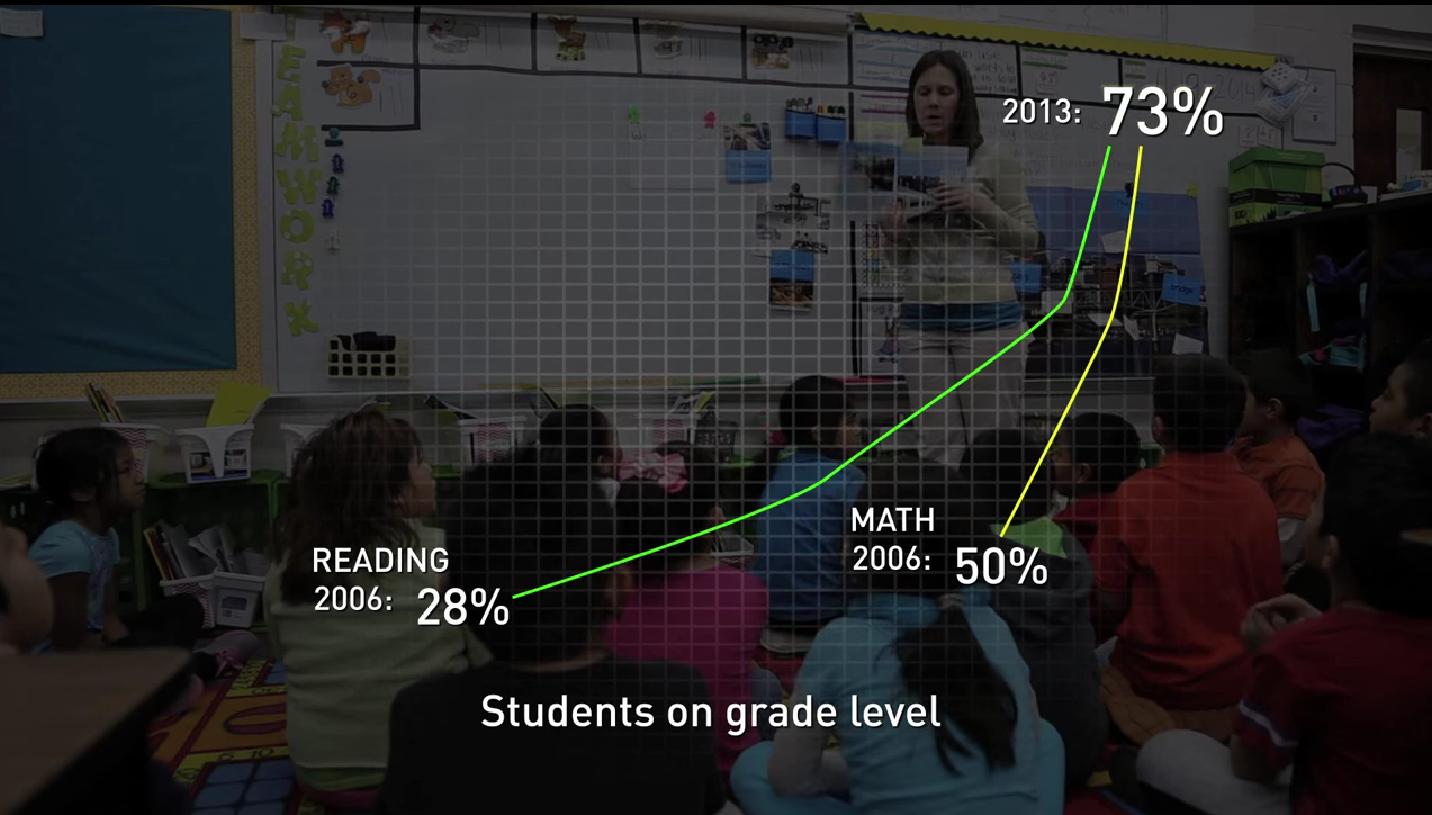

And the results are quite dramatic:

The above does appear quite convincing. Teamwork leads to better schools. Until one comes across another blog. This one is from TeachThought. The following is an excerpt:

When we ask for great teachers, then, it’s not clear if we all mean the same thing when we use the term. What’s a great teacher? If nothing else, by definition a great teacher is going to be exceptional. Different. If everyone is extraordinary, no one’s extraordinary.

A great teacher navigates the boundaries of policy, content, and the sensitivity of people to get the clearest view of students. The most important gift a teacher has is the ability to see children for who they are, who they can be, and the relationship between the two. They have the unique ability to see students and content and thought and ideas and then nothing else—a blindness to irrelevance that lets the rest of the world melt away. They see your literacy plan, and your assessment policy, and your hashtag, and your app—but they see it within a macro context that it doesn’t matter—and can’t survive–without.

This means that they might not “buy-in” to the new district initiatives. They may question the $500,000 iPad “rollout.” They might resist the testing if all of the data is just going to sit there without substantively altering future curriculum and instruction. They may not be the stars of the PLC.

And unless they have enough charisma to pull it all off, it’s all going to cost them their “team-player” reputation.It is a false dichotomy. Even in sports, a great basketball player is likewise a great team player. Problems often creep into the picture for other reasons. Teamwork only provides an environment where strengths can be shared and weaknesses addressed. The phrases mentioned above are all sound and good but these all lose luster in the face of pretense or incompetence. The fact that a great teacher is one who is able "to see students and content and thought and ideas and then nothing else" means that one simply has to keep in mind that the goal is not to be a dream team, but to teach children.

Echoing Alfie Kohn's sentiment:

A skunk cabbage by any other name would smell just as putrid. But in education, as in other domains, we’re often seduced by appealing names when we should be demanding to know exactly what lies behind them. Most of us, for example, favor a sense of community, prefer that a job be done by professionals, and want to promote learning. So should we sign on to the work being done in the name of “Professional Learning Communities”? Not if it turns out that PLCs have less to do with helping children to think deeply about questions that matter than with boosting standardized test scores.

Comments

Post a Comment