Why Basic Education Must Not Be Run By Market Forces and Strategies

In the stock market, the week during which most public companies report their earnings provides suspense and anticipation among traders and investors. There is a bottom line and that is profit. A business that is profitable means good business. Perhaps, it is the unwavering focus on the bottom line that makes some people think that market thinking is applicable to other human endeavor like basic education. After all, education outcomes can be regarded as similar to profits. There is the belief that the efficiency and competition that markets impose on businesses can drive basic education in a similar fashion.

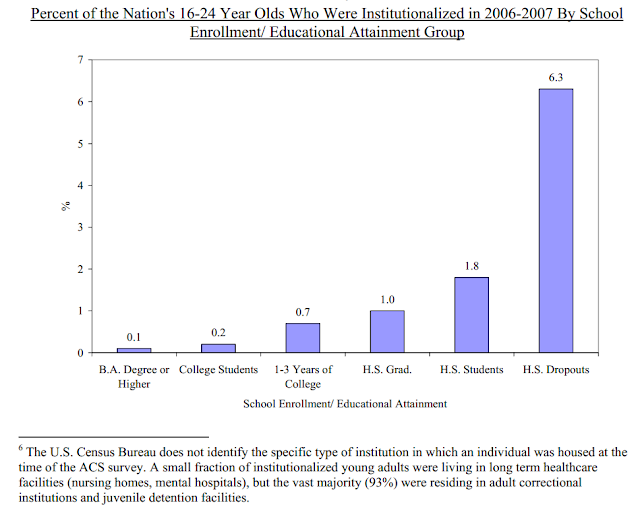

The main error with this thinking is that learning outcomes are so vastly different from profits. Basic education like public infrastructure serves society not just on an individual basis but as a whole. This one may be a crude analogy, but take, for example, a public restroom. I may not be using it, but since there is one, I need not worry while I walk around about stepping on something highly undesirable. In the United States, "the incidence of institutionalization problems among young high school dropouts was more than 63 times higher than among young four year college graduates (The Consequences of Dropping Out of High School):

Crimes not only affect the perpetrators and victims but society as a whole. For this reason, education must address equity. The quality of education a child of another parent can affect me, so much more than any product that parent bought for that child. Thus, although it is a crude analogy, it rings some truth.

Businesses need to maximize profits. To do so, one must use the least resources required so that the cost of production is at a minimum. Of course, one can also inflate the final selling price since the difference is the profit. Businesses, however, can not overprice without sacrificing the volume of sales. Thus, these features make such way of thinking appealing to apply on providing basic education. It minimizes waste and maximizes output, and the customer still has a say on what price is reasonable.

I am not in business and I have no training on market strategies, but the above seems quite naive.

There are strategies in business. One is market segmentation:

The following is borrowed from lecture notes of Prof. Fred Thompson of Williamette University:

Marketers can orient their products to customers in four distinct ways.

The main error with this thinking is that learning outcomes are so vastly different from profits. Basic education like public infrastructure serves society not just on an individual basis but as a whole. This one may be a crude analogy, but take, for example, a public restroom. I may not be using it, but since there is one, I need not worry while I walk around about stepping on something highly undesirable. In the United States, "the incidence of institutionalization problems among young high school dropouts was more than 63 times higher than among young four year college graduates (The Consequences of Dropping Out of High School):

|

| Above figure copied from |

Crimes not only affect the perpetrators and victims but society as a whole. For this reason, education must address equity. The quality of education a child of another parent can affect me, so much more than any product that parent bought for that child. Thus, although it is a crude analogy, it rings some truth.

Businesses need to maximize profits. To do so, one must use the least resources required so that the cost of production is at a minimum. Of course, one can also inflate the final selling price since the difference is the profit. Businesses, however, can not overprice without sacrificing the volume of sales. Thus, these features make such way of thinking appealing to apply on providing basic education. It minimizes waste and maximizes output, and the customer still has a say on what price is reasonable.

I am not in business and I have no training on market strategies, but the above seems quite naive.

There are strategies in business. One is market segmentation:

|

| http://www.marketsegmentation.co.uk/ |

Marketers can orient their products to customers in four distinct ways.

- Mass marketing aims to attract all kinds of buyers by producing and distributing the one best product at the lowest possible price

- Segment or product-variety marketing aims to serve large identifiable groups by offering a limited array of good products at a variety of prices.

- Target (both niche and local) marketing aims to please identifiable clusters of customers by providing products that are carefully tailored to match group means and tastes.

- Individual or marketing aims to satisfy individual customers by providing products that are precisely tailored to match individual means and tastes.

Indeed, browsing through a BestBuy web page illustrates how different products are designed to target different types of buyers. Take, for example, refrigerators:

|

| Refrigerators from BestBuy |

Market segmentation can take into account any of the following:

Segmentation Criteria

|

| Jobber, David. (2004) Principles and practice of marketing, 4th edition, the McGraw-Hill Co. |

Bill Ferriter actually uses refrigerators to argue that business practices are not suited for basic education in a recent blog article, "Here's Why Competition Doesn't Work in Public Education". The following are excerpts:

Real-live apple-pie eating, baseball loving American businessmen are trying to carve out a space for themselves in SPECIFIC markets, producing refrigerators for certain KINDS of customers. Some — like Subzero — are producing high end refrigerators for people who own $500,000 homes and are ready to drop a few grand on top end appliances that will serve as centerpieces in their kitchens. Others — like Kenmore — don’t even bother with the bells and whistles, instead focusing their attention on developing functional-but-not-fancy machines for people like you and I.

And then there’s guys like Joe — the landlord who showed up in my driveway when he noticed the delivery truck bringing our new refrigerator to our house.

“Hey — have you got an old unit you’re trying to get rid of? I’d be happy to take it off your hands,” he said. I told him that he wouldn’t want my refrigerator. It was 20+ years old, had been sitting unplugged in my backyard for about two weeks, had been rained on three times, and barely kept anything cold anymore.

“That don’t matter,” he said. ”I rent houses out in the poor section of town. As long as it blows a little cool air, those people will be happy. I’ll give you $50 bucks and haul this thing away right now.”

Joe has figured out competition, hasn’t he? He’s identified a marketplace — “those people in the poor section of town” — that no one is serving. Then, he’s figured out just how much he has to spend to keep his customers happy.Business will develop schools equipped with all the bells and whistles for those who can afford. These will be the "Subzero" version of schools. On the other hand, schools like the old, used, and barely running refrigerators Joe buys will be provided to low income families. Ferriter then ends his article with an insightful statement:

While the quality of other people’s refrigerators doesn’t affect ME in a deep and meaningful way, the quality of their education most certainly does. Ensuring that ALL children — including “those people living in the poor section of town” — have access to Subzero schools means ensuring that ALL children will grow up to be competent citizens ready to make positive economic and social contributions to our communities.

That’s an outcome we should ALL care about — capable neighbors really DO fuel economic growth and ensure a healthy future for everyone — but it’s an outcome that competition doesn’t automatically advance.McKinsey and Company stated in a report in 2009:

“ These educational gaps

impose on the United States

the economic equivalent of

a permanent national recession.”

Comments

Post a Comment