Fordham Institute's Final Evaluation of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)

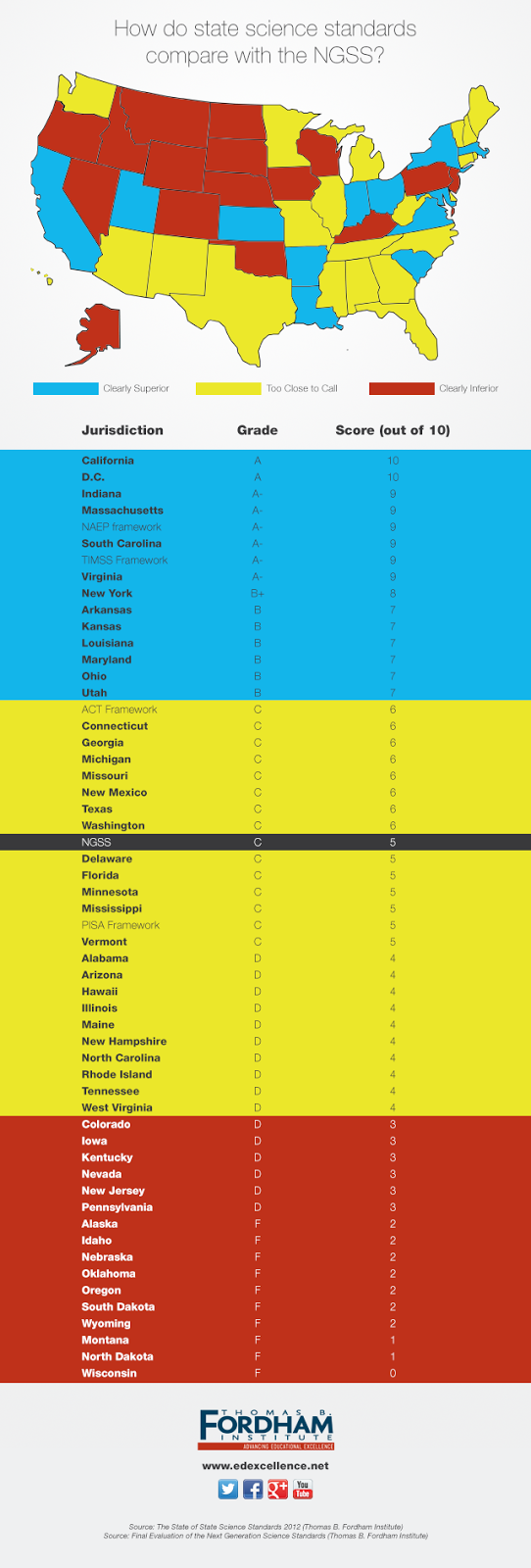

The New Science Standards drafted for US K-12 public schools did not earn high marks from the Fordham Institute. The following figure summarizes where the Institute thinks the new standards stand in comparison with science curricula currently implemented in the various states:

|

| http://www.edexcellence.net/publications/final-evaluation-of-NGSS.html |

Here is an excerpt from the final review that carries the overall sentiment of the report (It contains quotes from Willingham and Hirsch, whose articles have already been mentioned and featured in this blog):

Good science consists of doing as well as knowing, of practices as well as content and concept, and well-taught K–12 science has long understood and incorporated this truth. But doing it well requires a careful balance that seems somehow to have eluded the NGSS authors. Instead, they conferred primacy on practices and paid too little attention to the knowledge base that makes those practices both feasible and worthwhile.

This error is often and easily made by experts who themselves have long since learned the content and who see their fellow experts engaging in interesting practices on a regular basis because they, too, already possess the requisite knowledge.But schoolchildren must acquire that knowledge in order to put it into practice. And their schools and teachers must make certain that this happens.

This is something that education pioneers like E. D. Hirsch, Jr. and cognitive scientists like Daniel Willingham have repeatedly and convincingly argued. “There is a consensus in cognitive psychology,” Hirsch explains, “that it takes knowledge to gain knowledge.”

Even more critically, Willingham argues that “those with a rich base of factual knowledge find it easier to learn more—the rich get richer” and that factual knowledge [actually] enhances cognitive processes like problem solving and reasoning. The richer the knowledge base, the more smoothly and effectively these cognitive processes—the very ones that teachers target—operate. So, the more knowledge students accumulate, the smarter they become.

The purpose of K–12 science standards, therefore, is not primarily to encourage mastery of “practices” or to encourage “inquiry-based learning.” Rather, the purpose is to build knowledge first so that students will have the storehouse of information and understanding that they need to engage in the scientific reasoning and higher level thinking that we want for all students.

Unfortunately, the NGSS suffer from the belief—widespread among educators—that practices are more important than content. Consequently, every standard in NGSS articulates a practice first, even when doing so obscures the content that students should learn. And, while there are stand-alone standards that list practices and skills that students must master, there are no standalone expectations that list—in clear, teacher-friendly language—the content that students should learn. Throughout the NGSS, content takes a backseat to practices, even though students need knowledge before they’ll ever demonstrate fluency or mastery of scientific practices.

Comments

Post a Comment