Cursive Handwriting, No Longer Necessary?

As I watch my son type "How long are wolves' canines?" on Google in his quest to compare wolves teeth against those of big cats, I wonder if the digital age has indeed paved the way for cursive writing to be a thing of the past. With a smart phone or an android tablet, my son could accomplish so many tasks by simply pressing or swiping the tiny screen in these gadgets. Sherry Posnick-Goodwin of the California Teachers Association writes:

"Should fancy loops and flowing letters of cursive still be taught to students? Is cursive writing an obsolete skill no longer relevant in today’s technological society?

The new Common Core State Standards for English do not require cursive. However, under the new standards, states are allowed to teach cursive if they choose, and California still does. Some states, like Georgia, are considering abandoning longhand lessons altogether, since cursive is not on standardized tests."

|

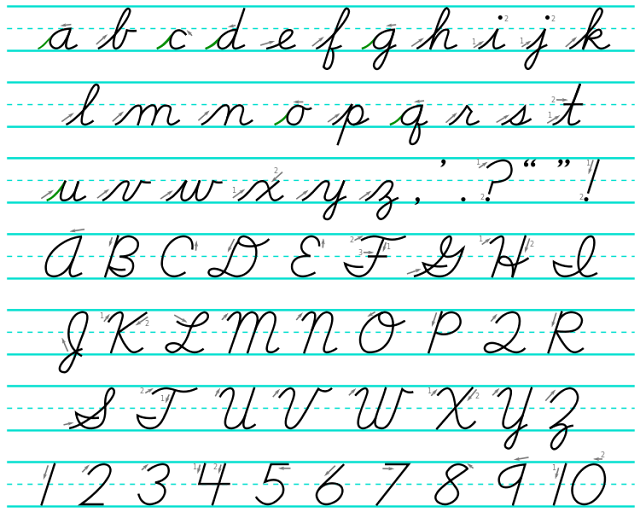

| Is Cursive Writing a Thing of the Past? Above image downloaded from Wikipedia |

Because the brain’s language systems have no end organs for interacting directly with the external world, language systems work with sensory (ears or eyes) and motor (mouth and hands) systems, which are the only brain systems with direct links to external environment. Liberman contributed to understanding of how the language by ear (listening) and language by mouth (reading) systems work together at the behavioral level and also become integrated to support acquisition of language by eye (reading) [1]. Berninger and colleagues extended the work of Liberman and colleagues at the Haskins Laboratory to language by hand (writing), which is not just a motor skill as many assume [2]. This University of Washington research team also showed that Language by Ear, Language by Mouth, Language by Eye, and Language by Hand are separate, but interacting functional language systems, which draw on common as well as unique processes at the behavioral [3] and brain levels of analysis [4]. Moreover, each of the functional language systems has different levels of organization, ranging from subword, to word, to syntax, to text, and has connections with other brain systems such as working memory, attention and executive functions, and cognitive.In a Wall Street Journal article, Berninger's research findings on writing is described in layman's terms:

Other research highlights the hand's unique relationship with the brain when it comes to composing thoughts and ideas. Virginia Berninger, a professor of educational psychology at the University of Washington, says handwriting differs from typing because it requires executing sequential strokes to form a letter, whereas keyboarding involves selecting a whole letter by touching a key.

She says pictures of the brain have illustrated that sequential finger movements activated massive regions involved in thinking, language and working memory—the system for temporarily storing and managing information.

And one recent study of hers demonstrated that in grades two, four and six, children wrote more words, faster, and expressed more ideas when writing essays by hand versus with a keyboard.Another paper worth noting in this field comes from cognitive scientists in France. The paper published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, "Learning through Hand- or Typewriting Influences Visual Recognition of New Graphic Shapes: Behavioral and Functional Imaging Evidence", has the following abstract:

Fast and accurate visual recognition of single characters is crucial for efficient reading. We explored the possible contribution of writing memory to character recognition processes. We evaluated the ability of adults to discriminate new characters from their mirror images after being taught how to produce the characters either by traditional pen-and-paper writing or with a computer keyboard. After training, we found stronger and longer lasting (several weeks) facilitation in recognizing the orientation of characters that had been written by hand compared to those typed. Functional magnetic resonance imaging recordings indicated that the response mode during learning is associated with distinct pathways during recognition of graphic shapes. Greater activity related to handwriting learning and normal letter identification was observed in several brain regions known to be involved in the execution, imagery, and observation of actions, in particular, the left Broca's area and bilateral inferior parietal lobules. Taken together, these results provide strong arguments in favor of the view that the specific movements memorized when learning how to write participate in the visual recognition of graphic shapes and letters.I guess at this point, there is a probably wisdom behind the Common Core stopping short of dropping cursive writing in schools. The Common Core just made it optional. But now that this is optional, it is important to take note of the above research findings. The Philippines' DepEd K to 12 curriculum also spends time only on oral fluency in the early years. The psychological findings of how the brain develops with language by mouth, ear, eyes and hands should bring pause to any program that neglects any one of these mechanisms.

Comments

Post a Comment