Problem Solving Before Instruction

While there is no doubt that direct instruction is most effective in education, improving its effectiveness remains an important area for research. Another question in education is the usefulness of homework. Although this has already been settled in research in some cases, one still wonders how and why homework is useful in higher education. Learning, as opposed to teaching, does occur inside the mind of a student. Thus, work done individually by a student must still have an effect on learning. One promising avenue that tackles both areas involves "problem solving before instruction" or PSI. Loibl and coworkers have summarized research on PSI and have suggested a "productive failure" mechanism that includes prior knowledge activation, awareness of knowledge gaps, and recognition of deep features.

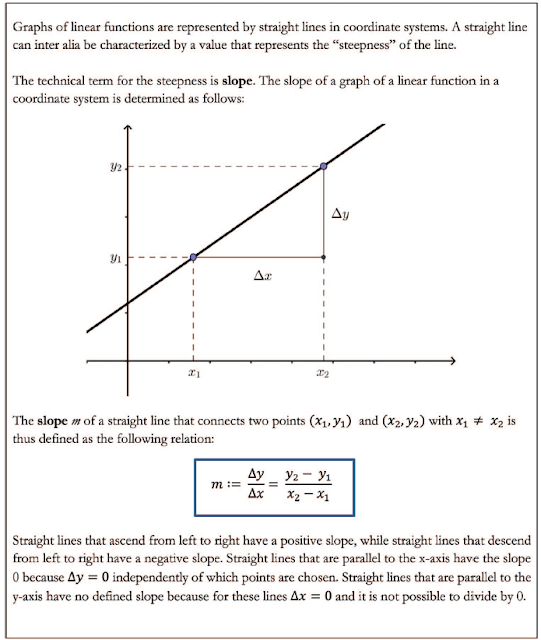

Doing a quantitative research on how well PSI works is of course extremely challenging. The topic or subject could easily be a factor. Obviously, the teacher is also important. Thus, at the moment, the best we can have are preliminary investigations that can probably provide a rough overview of whether such practice is beneficial or not. One such study is a recent work scheduled to be published in the Journal of Educational Psychology. In this work, a specific lesson on slopes is considered for more than 200 ninth-graders in Switzerland. The students are divided into five groups, one group is assigned to the traditional "Tell and Practice" in which instruction comes first before problem solving. The other four start with problem solving first and these differ from each other in terms of what is asked of the student: self-explain or invent, and the type of problems: grounded (specific) or idealized (general). To remove the effects of the teacher, the instruction involves a 5-minute period during which the student is asked to read the following:

The researchers find that not all PSI are superior to "Tell and Practice", especially when it comes to a later test, four weeks after the instruction.

Doing a quantitative research on how well PSI works is of course extremely challenging. The topic or subject could easily be a factor. Obviously, the teacher is also important. Thus, at the moment, the best we can have are preliminary investigations that can probably provide a rough overview of whether such practice is beneficial or not. One such study is a recent work scheduled to be published in the Journal of Educational Psychology. In this work, a specific lesson on slopes is considered for more than 200 ninth-graders in Switzerland. The students are divided into five groups, one group is assigned to the traditional "Tell and Practice" in which instruction comes first before problem solving. The other four start with problem solving first and these differ from each other in terms of what is asked of the student: self-explain or invent, and the type of problems: grounded (specific) or idealized (general). To remove the effects of the teacher, the instruction involves a 5-minute period during which the student is asked to read the following:

The researchers find that not all PSI are superior to "Tell and Practice", especially when it comes to a later test, four weeks after the instruction.

First, the test results are not really that good overall. The highest mean score among the groups is roughly 65% correct. My students for instance in my General Chemistry are not going to be satisfied with such results. The reason why the test scores in this study are low is its difficulty given what is taught to the students. Below is an example of the questions in the test.

A straight line goes through the point (x, y). Is it right or wrong to say that the slope equals y/x? Give an explanation!Second, the topic covered here is very important in basic education. In fact, my son who is currently in sixth grade already works on this. Nonetheless, due to the importance of slopes in math and the sciences, students are only bound to encounter this concept so many times during their schooling. And because of its importance, one can just imagine how easy it is to extend slopes to almost any problem. It may have been better if the study has picked a less general concept. Third, it uses reading as a substitute for direct instruction. This short instruction is static and therefore not capable of responding specifically to where the students are, as opposed to a teacher who has the capacity to tailor the instruction depending on the outcome of the initial problem solving. It is therefore amazing that even with these limitations, the researchers still manage to find some benefit in Problem Solving Before Instruction.

An academic textbook is different from a novel. Listening to a lecture is equally different from watching a movie. Therein lies the possible benefits of Problem Solving Before Instruction. Attempting to solve problems before reading a textbook or attending a lecture can give a student a much more engaging perspective. "Productive failure" corresponds to questions that need to be answered. A student can therefore end up searching and not just skimming. And in a lecture hall, a student may end up listening and not just hearing.

Comments

Post a Comment