When We Choose What We Cite

This evening, the advisory committee for advanced academic programs in Fairfax county will finalize its recommendations. For about a year, this committee has listened to presentations, has viewed some relevant data, and has seen some primary literature. Nonetheless, with just one meeting each month, it is unlikely that the committee has seen everything that needs to be considered to make recommendations. Moreover, as in any group, there are "knowledge brokers" and oftentimes, instead of drawing policies or recommendations from research-based evidence, policy-based evidence becomes the choice. Unlike in chemistry or in other physical sciences, in education, we often choose what we cite. Our meetings therefore simply become echo chambers and the public could suffer from not knowing the truth.

The introduction of the new K-12 curriculum in the Philippines is an excellent example. In A critique of some commentaries on the Philippine K-12 program, Flor Lacanilao lamented "...the comments of scientists on the Philippine K-12 program are supported by properly published studies or authorities, whereas those by nonscientists are not. Note further that the nonscientist authors and cited authorities include prominent people in education, and that these nonscientist authors and cited authorities enjoy wide media coverage. I think this situation explains the present state of Philippine education."

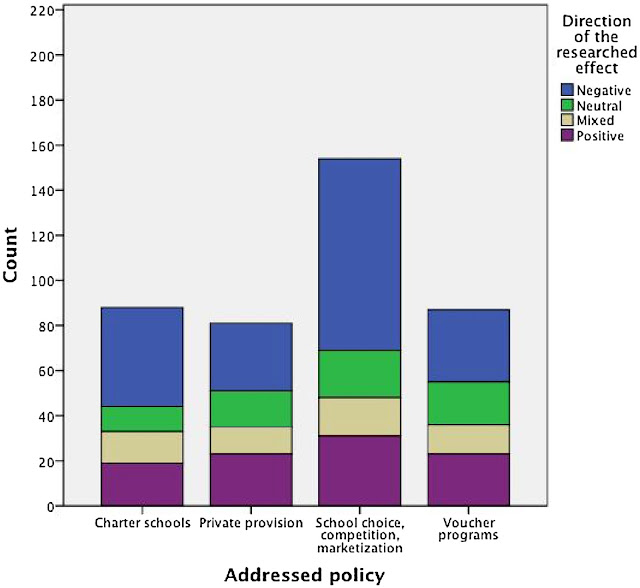

And the Philippines, unfortunately, is not an exception. Highly influential international agencies such as the World Bank demonstrate likewise a scenario where evidence-based policy making is completely illusory as shown by Antoni Verger and coworkers in a paper recently published in the International Journal of Educational Development. The specific issue Verger and his team examined is the case of education privatization. We hear often that giving parents school choice, allowing for greater private partnerships and charter schools, and distributing vouchers are good for basic education. The World Bank supports these ideas and makes the claim that these are endorsed by evidence from research. This is false as negative effects from privatization are actually more predominant:

In the physical sciences, this will be regarded clearly as dishonesty. But as Verger and coworkers point out:

In the Philippines, no one will be really held accountable for the disastrous K to 12 curriculum. And in Fairfax county, advisory committees will always be influenced by what they choose to see.

The introduction of the new K-12 curriculum in the Philippines is an excellent example. In A critique of some commentaries on the Philippine K-12 program, Flor Lacanilao lamented "...the comments of scientists on the Philippine K-12 program are supported by properly published studies or authorities, whereas those by nonscientists are not. Note further that the nonscientist authors and cited authorities include prominent people in education, and that these nonscientist authors and cited authorities enjoy wide media coverage. I think this situation explains the present state of Philippine education."

And the Philippines, unfortunately, is not an exception. Highly influential international agencies such as the World Bank demonstrate likewise a scenario where evidence-based policy making is completely illusory as shown by Antoni Verger and coworkers in a paper recently published in the International Journal of Educational Development. The specific issue Verger and his team examined is the case of education privatization. We hear often that giving parents school choice, allowing for greater private partnerships and charter schools, and distributing vouchers are good for basic education. The World Bank supports these ideas and makes the claim that these are endorsed by evidence from research. This is false as negative effects from privatization are actually more predominant:

In the physical sciences, this will be regarded clearly as dishonesty. But as Verger and coworkers point out:

In this regard, the education policy marketplace is quite unlike other evidence-based domains. In education, there are few requirements for vigilance, and there is no accountability for adverse events. The merchant is responsible only for the promotion of the idea – and is not held into account after that. If an agency is updating a report on a policy solution such as PPPs in education, there is no requirement to include negative or critical reports. This phenomenon of filtering out negative effects has been documented in the academic literature, including our case study presented here, and termed as “policy-based evidence” or as “the echo chamber” effect, where literature reviews and agency reports include concurring ideas and select out dissent. The impact of such echo chambers carries serious risk, in that it distorts reality to create an uncharacteristically favourable outlook.

In the Philippines, no one will be really held accountable for the disastrous K to 12 curriculum. And in Fairfax county, advisory committees will always be influenced by what they choose to see.

Comments

Post a Comment