"I already know so this must happen" versus "This is what I see, now, I know."

Lions sometimes hunt elephants. The deadliest animal in the world is the mosquito. After all, the female Anopheles mosquito is the vector of one of the world's deadliest disease, malaria. These are few examples of facts that bring astonishment to my son's young mind. These carry an element of surprise because even at an early age, a child is already developing a library of information in his mind. Psychologists would characterize a child's way of thinking as mostly "experiential". It is fast. It relies mostly on memory. Learning or being exposed to something new that seems to be out of place in that small library inside a human mind challenges human thinking. It is at this point when the human mind must make an adjustment. It is the beginning of what psychologists refer to as "analytic" processing.

Science is both "experiential" and "analytic". For this reason, science education in the early years is important for it provides an excellent opportunity for children to discover "analytic" processing. The inability to do "analytic" processing can later lead to stubborn misconceptions that can continue well into adulthood. "Lions do not hunt elephants in the wild, these videos are simply staged", or "Mosquitoes are not the deadliest since malaria is not a global health problem, this is simply a conspiracy manufactured by the World Health Organization." These are responses that may come from a person who is completely convinced of one's "experiential" knowledge or what others may refer to as intuition. Scientific thinking does begin with intuition. It starts with a hypothesis or a guess. Science, however, tests the hypothesis. It is during this testing that human thinking becomes more conscious or deliberate. In this realm, it is no longer "How do you feel about this?" or "What is your initial impression?". During testing it is purely about "What is really happening?"

At about the age of 4, children are beginning to develop executive function in their brain. Executive function is a set of mental processes that helps connect past experience with present action. People use it to perform activities such as planning, organizing, strategizing, paying attention to and remembering details, and managing time and space (National Center for Learning Disabilities). In young children, the development of executive function manifests in the following. At three to four years, children can sort objects according to shape or according to color, as long as the sorting is done based on only one rule, either shape or color, but not both. Progress in executive function is seen when a child is able to switch between rules. The development in executive function in doing science is much more profound since it does not really involve a switch between made-up rules like sorting according to shape or color. The rules are real. Science requires a switch from "I already know so this must happen" to "This is what I see, now, I know."

Jess Gropen and colleagues argue that science education is important in early childhood education by illustrating that learning science at such age is timely for the rapidly developing executive function of a child's mind. It is an opportunity not to be missed. In their argument, the authors cite previous research and summarize these in an article published in the journal Child Development Perspectives. The abstract of the article, "The Importance of Executive Function in Early Science Education" is as follows:

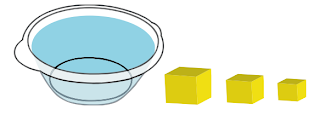

The children are then asked to provide their initial guess from the following choices. And most picked the smallest cube to sink:

Children are then allowed to observe what actually happens:

Children are also asked to reflect and compare their guess with the observation.

It takes some level of consciousness in fact to realize and accept that the initial guess is really different from the observation. This is the point when a discrepancy is experienced between what a child thought he or she knew and what actually happened. Recognizing the difference between a "belief" and "reality" is an important milestone in scientific thinking. Gropen et al. emphasize that this recognition is no different from other processes described as executive function. Whether a child has indeed developed this skill can be seen in an additional activity where a child is presented the following:

where one could choose any of the cylinders to be made of steel, and see which one a child picks.

This is a simple activity, yet so pedagogically profound....

Science is both "experiential" and "analytic". For this reason, science education in the early years is important for it provides an excellent opportunity for children to discover "analytic" processing. The inability to do "analytic" processing can later lead to stubborn misconceptions that can continue well into adulthood. "Lions do not hunt elephants in the wild, these videos are simply staged", or "Mosquitoes are not the deadliest since malaria is not a global health problem, this is simply a conspiracy manufactured by the World Health Organization." These are responses that may come from a person who is completely convinced of one's "experiential" knowledge or what others may refer to as intuition. Scientific thinking does begin with intuition. It starts with a hypothesis or a guess. Science, however, tests the hypothesis. It is during this testing that human thinking becomes more conscious or deliberate. In this realm, it is no longer "How do you feel about this?" or "What is your initial impression?". During testing it is purely about "What is really happening?"

At about the age of 4, children are beginning to develop executive function in their brain. Executive function is a set of mental processes that helps connect past experience with present action. People use it to perform activities such as planning, organizing, strategizing, paying attention to and remembering details, and managing time and space (National Center for Learning Disabilities). In young children, the development of executive function manifests in the following. At three to four years, children can sort objects according to shape or according to color, as long as the sorting is done based on only one rule, either shape or color, but not both. Progress in executive function is seen when a child is able to switch between rules. The development in executive function in doing science is much more profound since it does not really involve a switch between made-up rules like sorting according to shape or color. The rules are real. Science requires a switch from "I already know so this must happen" to "This is what I see, now, I know."

Jess Gropen and colleagues argue that science education is important in early childhood education by illustrating that learning science at such age is timely for the rapidly developing executive function of a child's mind. It is an opportunity not to be missed. In their argument, the authors cite previous research and summarize these in an article published in the journal Child Development Perspectives. The abstract of the article, "The Importance of Executive Function in Early Science Education" is as follows:

This article argues that executive function (EF) capacity plays a critical role in preschoolers’ ability to test and revise hypotheses and, furthermore, that young children can engage in the process of testing hypotheses before they are able to revise or confirm them. Research supports the view that this ability depends on their EF capacity to represent, and reflect on, hierarchical rules relating actions to predicted or observed outcomes (i.e., differences between what they predicted and what they observed). The article concludes by discussing the ramifications of this perspective for early science education.One specific science lesson or activity that the article describes is an experiment involving three blocks, all colored yellow, but different in size. The largest and smallest ones are made of wood while the medium sized block is made of steel. A bowl containing water that is artificially colored blue is provided and a student is asked which of the blocks will sink, and which one(s) will float (The following figures are all copied from "The Importance of Executive Function in Early Science Education":

The children are then asked to provide their initial guess from the following choices. And most picked the smallest cube to sink:

Children are then allowed to observe what actually happens:

Children are also asked to reflect and compare their guess with the observation.

This is a simple activity, yet so pedagogically profound....

the term basic education has long been understood to begin at some sort of formal classroom setting...basic education must and should be much earlier than that...the parent's basic understanding that they are conceiving a life form that is much much superior that all the other creatures on earth...a human being with a human body and soul which must be educated simultaneously...

ReplyDeleteDo we need parent education? Should parents be trained for early childhood education?

ReplyDelete